Agnieszka Roguski

Proliferating Infrastructures

GOSSIP as speculative institutional narrative

Gruß aus der Lockstedter Lager, postcard, 1918

When I began my time as Artistic Director at the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, I entered more than just an exhibition space. With the position, I stepped into an institutional history that not only addressed the military past of the municipality of Hohenlockstedt, as the name of the Foundation’s exhibition space – M.1, an abbreviation for Military Barracks 1 – revealed, but also the history of the Boskamp family, as well as that of the pharmaceutical company Pohl-Boskamp and the history of the Foundation’s Artistic Directors, who have been changing on a rotating basis since 2007. From the Foundation’s entanglements with various local and supra-regional actors, past and present, an institutional narrative emerged that at first seemed as complex as it was inscrutable. I myself became part of a structure that followed different infrastructures: communal, familial, economic as well as institutional. The self-image of the institution seemed confused; a communal agenda mixed with contemporary discourses of the international art world. I was told that the Foundation was perceived as an “UFO” in the town. Situating my own perspective exemplarily in the M.1 of the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, I asked myself: if an institution can be perceived as an UFO, what stories and speculations contribute to its narrative? And how do the multi-layered and entangled infrastructures of an institution form accordingly? Setting my perspective as a curator exemplary is first to understand my own positionality as relationally embedded in various institutional processes. This refers to an understanding of subjectivity embedded in infrastructures and relationships with human and non-human actors. Consequently, the stakes I would make with my curatorial program were no more tied to my authorship than merely following a given institutional narrative – they developed out of a subjective engagement with the place. Philosopher and feminist theorist Rosi Braidotti states accordingly: “While identity is a limited, ego-indexed habit of fixing and capitalising one’s self, subjectivity is a socially mediated process of relations and negotiations with multiple others and with multilayered social structures.” 1 In terms of a posthuman, relational understanding of multi-layeredness and coherence, therefore, institutional infrastructures in particular proliferate – and thus perpetuate their narratives. Against this background, infrastructures are not a given, they grow and proliferate because they are always in resonance with daily actions. In this sense, Lauren Berlant defines infrastructure “by the movement or patterning of social form. It is the living mediation of what organizes life: the lifeworld of structure.” 2 As such, infrastructures are never completely invisible, but rather mark visible signals to create transport routes, facilitate administrative processes or plug communication gaps. Nevertheless – or precisely because of their omnipresent visibility – they often fade into the background; who thinks of the software that fills windows with text during a chat? The email inboxes of curators while visiting an exhibition? As ‘silent’ conditions for ‘noisy’ artworks, infrastructures are outsourced to the level of the systemic. This overlooks the fact that the dimensions of institution, infrastructure, architecture and interface always represent a form of active involvement rather than merely acting as a passive condition. Taking a performative, action-oriented interpretation of infrastructures as a starting point, I was interested in everyday practices that co-formulate institutional infrastructures as well as the archive of institutional narratives that in this way continuously grows with them. This led me to the study of the phenomenon of gossip, an everyday practice often dismissed as inferior, whose presence in the narrative of an institution is usually neither explored nor even acknowledged. Scandals involving executives are an exception – but as a conscious strategy or self-(re)produced part of an institution’s image, gossip hardly receives any attention. Gossip, I claimed with my annual curatorial program of the same name in 2021, makes institutional infrastructures and memories visible that were otherwise barely noticed. How does gossip thus institute an ephemeral, invisible archive of an institutional narrative? And how does this archive resonate with communal infrastructures?

1 Braidotti, Rosi: From Nomadic Theory. In: Aloi, Giovanni / McHugh, Susan (eds.): Posthumanism in Art and Science. New York: Columbia University Press 2021, 40-43, 40.

2 Berlant, Lauren: The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2016, Vol. 34(3), 393–419, 393.

3 See Federici, Silvia: Caliban and the Witch. New York: Autonomedia 2004, 221.

4 Black, Hannah: Witch-hunt. Gossip has always been a secret language of friendship and resistance between women. In: Tank Magazine / The Gossip Issue, Spring 2017, 107–110, 109.

5 Butt, Gavin: Between you and me – queer disclosures in the New York art world, 1948-1963. Durham: Duke University Press 2005.

6 Siegel, Marc: Gossip is fabulous. Queer Counter-Publics and “Fabulation”. In: Texte zur Kunst, Issue 61/ Gossip, March 2006, 116–121.

7 Siegel, Marc: The Secret Lives of Images. In: Hagener, Malte / Hediger Vinzenz / Strohmaier Alena (eds.): The State of Post-Cinema. Tracing the Moving Image in the Age of Digital Dissemination. London: Palgrave Macmillan 2017, 195–210, 196.

First of all, gossip was interesting to me precisely because it had negative connotations: as unauthorized, legitimate knowledge, as marginal, enigmatic, perhaps peripheral. To program an institution in a rural area meant working beyond the urban art centers with an audience whose knowledge of art was not necessarily pre-educated. I was in a context that was called periphery – but with the thematic setting on gossip, this context began to develop its own language and release knowledge. The narrative of the foundation was linked to a white man, the successful pharmacist and hobby artist Arthur Boskamp. This focus on the white male entrepreneurial figure was meant to be changed with GOSSIP. Accordingly, I referred to a definition of gossip as formulated by feminist and queer theorists. In “Caliban and the Witch,” Silvia Federici shows how in modern sixteenth-century England the term “gossip” was first used pejoratively to undermine exchange and solidarity among women*.3 During the Middle Ages, gossip was used to refer to a close female friend. Federici attributes this to the rise of capitalism, which excluded women* from the public sphere in order to exploit their reproductive labor, now understood as private, and to tie property relations to gender. Gossip was seen as an attack on these relations, as it formed an alliance between women* beyond the relationship of wife and husband – and, according to Federici, can be seen as perpetuating discrimination and persecution against women*, as was done with the witch hunts of the Middle Ages. For me, this devaluation was an important starting point, because it was followed by possibilities of solidarity and invisible alliances within and beyond institutions. I wanted to explore the resistance of gossip that is created through the formation of counter-publics; elusive, marginal publics based on trust rather than authorization, on informal gatherings and the uncontrolled circulation of content. When artist Hannah Black writes: “The gossip, like the witch, was persecuted as if she were an outlaw, instead of at the heart of her community. Her superpower is hanging out – giving, sharing, spending and wasting time together”,4 then I wanted to explore these gatherings as the perpetuation of a previously invisible archive on an institutional level as well. I related to queer and feminist approaches as Marc Siegel and Gavin Butt5 formulated also in reference to the art world. Siegel underlines the subversive power of gossip in queer subcultures of the 1980s6 and emphasizes its speculative momentum: “Gossip, I argue, is not simply a means of oral communication but rather a speculative logic of thought […] and central to the construction of identity and intimacy in queer counterpublics.”7 As a consequence, gossip has a performative and transformative effect on the relationships of individuals, institutions, and media; it changes one’s own self-images and narratives by circulating speculations about others. Taking a closer look at the projects that took place at the M.1 of the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung in Hohenlockstedt, this circulation and proliferation of narratives against the backdrop of both a very present family history and a public institutional mission became the core of the program GOSSIP in 2021. Working in a Foundation that is named after Arthur Boskamp and run by his daughter Ulrike Boskamp, I was facing the legacy of a family: their internal relationships and embeddedness in the region. More precisely, the absent eponym symbolizes next to his passion for art the history of the place itself, a history that is interwoven with the military, with the German economic miracle of the postwar years, and with power in general. When Arthur Boskamp took over his father’s business in 1945, he ordered the company to flee from Danzig to Schleswig-Holstein to escape the Red Army. In what was then Lockstedt Lager (today: Hohenlockstedt), he acquired former military quarters from the Kaiser era and began building the current company headquarters there to produce gelatin capsules and other cold preparations in a former SA sports school. I questioned, how could this embeddedness in the local history of military and capitalism speak back to the institution?

Understanding GOSSIP as a strategy of curatorial research, the development of mediation strategies that discuss, dismantle, and recompose the dominant narratives of the institution became the core of the program. These narratives were put in relation to vernacular, non-institutionalized forms of communication to explore their potential of instituting new narratives – thus disseminating a fluid, speculative archive of communal infrastructures. Taking the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung as an exemplary case study, GOSSIP investigated how those narratives are composed – and how they can be transformed into a speculative scenario. First of all, the narrative of the institution followed Arthur Boskamp on one hand, and the authorship of each Artistic Director on the other. Both were rooted in the patronage of an individual subject and in the role of the artist as creator. GOSSIP, I assumed, could queer these narratives by shifting the perspective from the role of the individual creator to the collective and decentralized act of storytelling. Queering here denotes the reiteration and reinterpretation of powerful fixed orders or (pre-)images, an “undoing [of] ‘normal’ categories,”8 as Donna Haraway calls it. Based on this focus on the parameter of gender, I use the term queer as an action practice of queering to reinterpret actions, gestures, and behaviors that follow white cis-male dominance, heteronormative structures, and a neoliberal logic through a curatorial program: a (re)ordering. My hypothesis was that within institutions, gossip functions as a form of invisible archive in relation to informal infrastructures that are constantly in motion, and that produce them under certain social, economic, and artistic conditions.

The programmes of each Artistic Director tell new stories about the institution with each directorship. Through such, the curatorial programmes create a narrative of continuous institutional flux. In this context, stories can be defined with Swedish literary theorist Lars Elleström as “a media product providing sensory configurations that are perceived in a meaningful way.”9 Stories are therefore less framing, but rather interpreting; they lay out a narrative in a sensually perceptible way and produce concrete, significant experiences. I linked these experiences in various formats to compose a specific dramaturgy, starting with one in which I myself would have no control over the plot of its story: an Instagram takeover of @m.1arthurboskampstiftung by students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig.

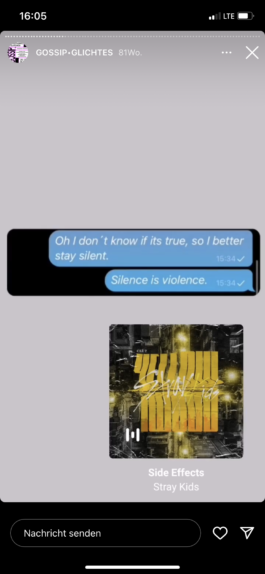

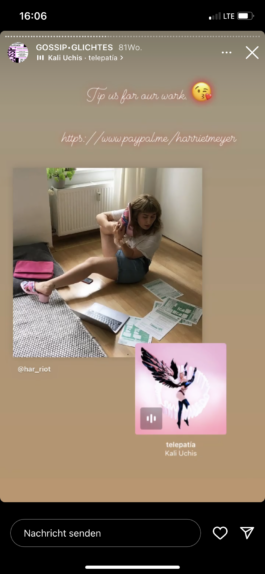

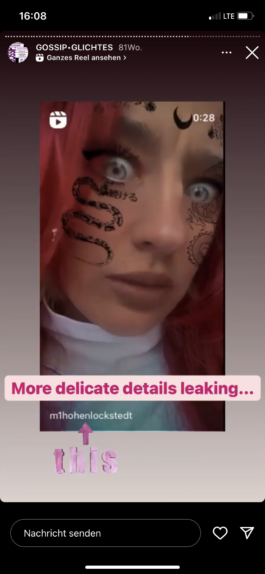

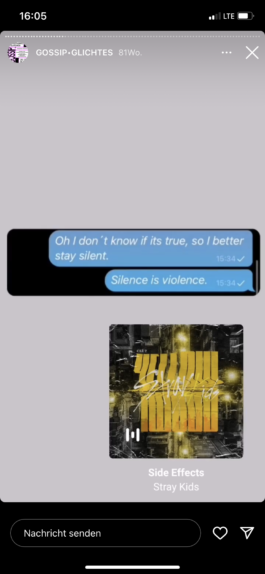

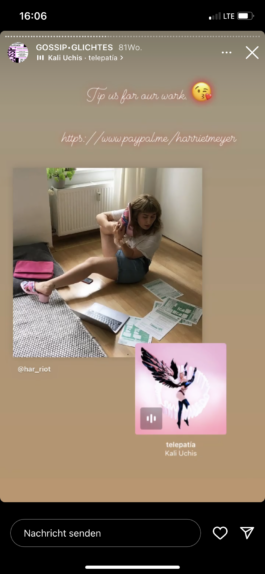

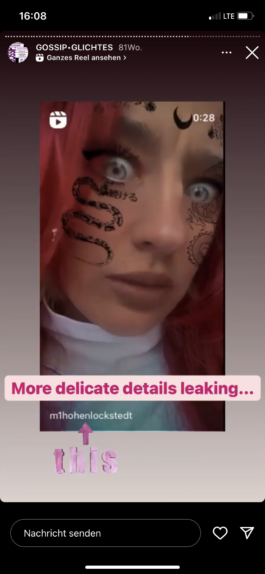

The first thing to queer my program was my own authorship. I took gossip programmatically, which meant I wanted gossip to determine the program. For this, content should become visible that was beyond my control, had a momentum of its own, and was not co-produced by the foundation. Following the determinant factor of time, the narrative of the foundation was described via Instagram with new stories at the start of the program. GOSSIP became a self-explanatory system error: it was not about the upcoming program within the foundation, but about debates within the Academy that were current at the time, such as the abuse of power and neoliberal productivity constraints. Under the title Institutional Glitches, the temporary takeover made clear that the circulation of manipulated information no longer takes place backstage, but has become an visible part of networked infrastructures in which institutions are also involved. Based on Legacy Russell’s notion of glitch10, the accidental error that indicates the radical failure of a system, the intervention accelerated and distorted the images of the foundation by shifting the narrative to the students’ personal needs and politics. Their inhabitation of the Instagram account showed how every system of representation is a multivocal system of intersubjective speaking positions that comment, repeat and rate each other. The narrative of the foundation, which I had been assigned to update and continue, initially dissolved into a cloud of social media buzz.11 Narration took place through communication and media products. It turned out that it was not the stories that changed – the students remained in the script of their university, so to speak – but the narrative within which they were articulated. The same story was thus transmitted in different narratives; but due to a shift of medium and speaking position, they could articulate critique in a transmedial way. “Silence is violence”, one of the posted stories claimed (Figure 2), made clear how the takeover contributed to an institutional archive of untold stories: stories that are not necessarily part of the foundation, but could traverse different institutions, stories that address systemic abuse of power positions, stories that made visible the immateriality of artistic work and unpaid labor by posting links to the students’ Paypal accounts (Figure 3). Sunny Pudert and Shirin Barthelt recorded videos, which hinted at explosive content without ever saying it. As a consequence, they continued with their Instagram Reels as a viral strategy to comment on the program. After the takeover and in cooperation with the online art magazine KubaParis, their dialogue-like clips were posted under the title The Gossipers, parodying the supposedly detached judgement of art criticism with strong filter aesthetics and effects (Figure 4).

8 Haraway, Donna: Foreword. Companion Species, Mis-recognition, and Queer Worlding. In: Giffney, Noreen (Hg.): Queering the Non/Human. Hamoshire und Burlington: Ashgate 2008, xxiii- xxvi, xxiv.

9 Elleström, Lars: Transmedial narratives and stories in different media. Cham: palgrave macmillan 2019, 35-43.

10 Russell, Legacy: Glitch Feminism. A Manifesto. London, New York: Verso 2020

11 David Joselt speaks about ‘buzz’ that defines the value of art in the digital age: “In place of aura, there is buzz”. Joselit, David: After Art. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press 2013, 16.

Fig. 2

Institutional Glitches, April 2021, Instagram screenshot

Fig. 3

Institutional Glitches, April 2021, Instagram screenshot

Fig. 4

Institutional Glitches, April 2021, Instagram screenshot

12 See Philips’ conception of storytelling as a scientific method of storytelling: Louise Gwenneth / Bunda, Tracey: Research through, with and as storytelling. New York: Routledge 2018, 1–16.

13 Lothian, Alexis: Old Futures. Speculative Fiction and Queer Possibility. New York: New York University Press 2018, 1–29.

14 Translated from the German original: „Geblieben ist ein großes Archiv und die Farbe Gelb, die jemand mochte. Und Arthur sah und sprach es werde Kunst, und es ward Kunst für einige. Und Arthur sah alles was er gemacht hatte und – . Doch heute gibt es M. und M. sind viele. In M. ist vieles anders und anders ist auch die Kunst.“

Fig. 5

Workshop THE SPECULATIVE INSTITUTION, M.1 Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, June 2021. Photo: Marie-Theres Böhmker

The first perception of my program was thus not a statement, as it is often done with exhibitions, but a loss of control that gossip often represents – and likewise the empowerment of voices that are not heard in this form in other infrastructures. I went further with this form of curating as an exploratory searching movement. I understood everyday stories as a scientifically and artistically relevant object that contrasts tested, situated knowledge with authorized narratives.12 In the sense of Louise G. Philipps and Tracey Bunda, storying, the verbification of the word story, advances to a counter-strategy of dominant narratives: stories live from being retold, from their communities, and have no superior scheme of meaning. It is based on local and situated truths. As a consequence of starting the program with a loss of control and increased social media traffic, I was interested in how the foundation’s narrative could be understood more as speculation directed into the future than as knowledge transmitted from the past. Since infrastructures usually anticipate the manifestation of future conditions, they are genuinely speculative scenarios.

Speculative scenarios often point to the digital, or to a fictional understanding of time, which above all conditions queer, non-linear chronologies.13 Chronologies are rarely interrogated in the self-image of institutions beyond a founding myth or a history of progress. Together with Fiona McGovern, I thus invited students of Cultural Studies and Cultural Mediation from the University of Hildesheim to take a closer look at the institutional narratives of the foundation. Based on locally situated and in-family, narrative-embedded stories, the students investigated how such stories were composed – and how they could be transformed into a potentially speculative scenario (Figure 5). The students developed a hypothetical mediation strategy consisting of an abstract, multi-vocal video conversation that highlighted a narrative that emerged from overlaps and superimpositions, anecdotes, gaps and questions. They combined image and text in a fragmentary and unfinished way. In doing so, they mixed different temporalities and speaker positions. Most of all, they rewrote and continued statements by Ulrike Boskamp, who had told the story of the foundation. The students combined history with storytelling and used these extracted, fragmentary anecdotes to refer affectively to individual places in the M.1, such as “the whirring of the refrigerator”. In this way, they created a new story that circulated around the institution, creating distance from the original narrative through the repetition of statements. The result was a subtle parody and critique in the form of a continuously moving text-image collage. For example, the students Nina Diehl, Leah Fot, Lisa Hader, Alina Homann and Theresa Tolksdorf referred to Arthur Boskamp and his position of power, from which he legitimized art – including his own – by exhibiting it, as well as the way the building is shaped by personal details such as his favorite color yellow. At the same time, they queered the narrative of Arthur Boskamp as founding father by opposing him with a multiple “M.” that cannot be traced back to one person, spoken in a fragmentary form:

“What remained was a large archive and the color yellow that someone liked

And Arthur saw and said let there be art, and there was art for some

And Arthur saw everything he had made and –

But today there are M., and M. are many

In M. many things are different and different is also the art”14

Critically questioning the relations of guest and host within institutions, the students discussed, dismantled, and speculatively recomposed dominant narratives, by making gaps in the history of the institution a visible part of their affective form of storytelling.

Fig. 6

QUEER BAR, M.1 Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, August 2021. Photo: Paul Niedermayer

A third example for the queered narrative of the institution is the project QUEER BAR. Hosted by the artist Paul Niedermayer,15 the QUEER BAR’s understanding of time, in the sense of Jack Halberstam, assumed that time is perpetually present. It is neither fixed on the reproduction of history nor on reproduction as its primary goal. Just as, according to Halberstam, queer time leaves frames of bourgeois reproduction and crosses different temporal planes,16 queer space leaves the binary logic of center and periphery to create counterpublics starting from the supposed margins. In the countryside, where queer people usually do not occupy much space in the sense of a visible, publicly accessible place, the QUEER BAR opened up the possibility of coming together at a shared, transgenerational community space. Through this coming together, it formulated resistance to prevailing narratives of invisibility of LGBTQI* persons in the countryside, while equally undermining a heteronormative understanding of time through the different generations. Against this background, Paul Niedermayer transformed the garden of the foundation into a bar in which familiar furnishing elements from local gastronomy were recombined with lighting elements and objects designed by the artist.

Each episode of the QUEER BAR contributed to both an existing and new infrastructure in continual creation of relationships, and blurred the boundaries between familiar and foreign. QUEER BAR signified queer possibilities for reinterpreting the present narrative, or the fiction of a possible future intertwined with the present. The bar’s resistant moment is its chrononormativity, the way in which experiences follow patterns over time in conformity with a (hetero)normative framework. This framework became recomposed by old elements; just like old stories that are re-told in order to create a new narrative. This narrative was community-based, queer, and never predictable: it continued from event to event by the guests themselves, who constituted the space through their conversations and stories. This ephemeral building of a queer community, often perceived as invisible in the countryside, became part of the institution’s archive and its infrastructures.

The formats of the social media takeover, the workshop and the bar reveal that institutional infrastructures are not merely a condition that can be used differently. They make clear that the way they are used reinterprets infrastructures and thus also retells them.

As events, they released space in different ways to queer the narrative of the foundation through exchanges, gatherings, conversations, and storytelling. Their invisible dimensions thus emerged and inscribed themselves in the Foundation’s ephemeral knowledge. Through their power-critical agenda, they told stories of otherwise locally invisible perspectives. They added alternative narratives to the site’s military and corporate history by formulating an infrastructure that defied control and calculation. This can be understood as a reiteration of invisible infrastructures already laid out by the Foundation, but were overwritten with authorship by the namesake, artists, and the curators. Gossip was thus deployed as a means of traversing different media and spaces and making this knowledge visible through new relationships. The field of the curatorial, which understands strategies of becoming public as forms of producing meaning by continuously rearranging and (re)combining contexts,17 can be seen as a method of making these – supposedly invisible – relations visible, and with them their political dimensions and infrastructural dispositions. In this sense, institutional narratives, just like gossip, have no clear origin, but unite object and addressee in a shared moment of re-telling. The narratives constituted by the program deviate from the institutional guidelines, which are strongly tied to persons – the respective Artistic Directors, as well as the eponym Arthur Boskamp. Rather, GOSSIP revealed how infrastructures always represent a form of common use that leads to new interpretations depending on expectations, perspectives of use, and medium. The image of the institution as a UFO, which I encountered at the beginning of my curatorship, is therefore the potential of the Foundation: it enables speculative, ephemeral modes of becoming visible of what was previously invisible.

15 Since 2022, the queer bar continues in a more self-organized way. It is organized by Agnieszka Roguski and Paul Niedermayer and co-hosted by people from the local queer community.

16 Halberstam, Jack [Judith]: In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives Sexual Cultures. New York & London: New York University Press 2005, 1-22.

17 Thus Beatrice von Bismarck states: “The curatorial is the dynamic field where the constellational condition comes into being.” Rogoff, Irit / von Bismarck, Beatrice: Curating/Curatorial. In: Bismarck, Beatrice von / Schafaff, Jörn / Weski, Thomas (Hg.): Cultures of the Curatorial. Berlin: Sternberg Press 2012, 21–38, 24.

Fig. 6

QUEER BAR, M.1 Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, August 2021. Photo: Paul Niedermayer

Agnieszka Roguski

Proliferating Infrastructures

GOSSIP as speculative institutional narrative

Gruß aus der Lockstedter Lager, postcard, 1918

When I began my time as Artistic Director at the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, I entered more than just an exhibition space. With the position, I stepped into an institutional history that not only addressed the military past of the municipality of Hohenlockstedt, as the name of the Foundation’s exhibition space – M.1, an abbreviation for Military Barracks 1 – revealed, but also the history of the Boskamp family, as well as that of the pharmaceutical company Pohl-Boskamp and the history of the Foundation’s Artistic Directors, who have been changing on a rotating basis since 2007. From the Foundation’s entanglements with various local and supra-regional actors, past and present, an institutional narrative emerged that at first seemed as complex as it was inscrutable. I myself became part of a structure that followed different infrastructures: communal, familial, economic as well as institutional. The self-image of the institution seemed confused; a communal agenda mixed with contemporary discourses of the international art world. I was told that the Foundation was perceived as an “UFO” in the town. Situating my own perspective exemplarily in the M.1 of the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, I asked myself: if an institution can be perceived as an UFO, what stories and speculations contribute to its narrative? And how do the multi-layered and entangled infrastructures of an institution form accordingly? Setting my perspective as a curator exemplary is first to understand my own positionality as relationally embedded in various institutional processes. This refers to an understanding of subjectivity embedded in infrastructures and relationships with human and non-human actors. Consequently, the stakes I would make with my curatorial program were no more tied to my authorship than merely following a given institutional narrative – they developed out of a subjective engagement with the place. Philosopher and feminist theorist Rosi Braidotti states accordingly: “While identity is a limited, ego-indexed habit of fixing and capitalising one’s self, subjectivity is a socially mediated process of relations and negotiations with multiple others and with multilayered social structures.” 1 In terms of a posthuman, relational understanding of multi-layeredness and coherence, therefore, institutional infrastructures in particular proliferate – and thus perpetuate their narratives. Against this background, infrastructures are not a given, they grow and proliferate because they are always in resonance with daily actions. In this sense, Lauren Berlant defines infrastructure “by the movement or patterning of social form. It is the living mediation of what organizes life: the lifeworld of structure.” 2 As such, infrastructures are never completely invisible, but rather mark visible signals to create transport routes, facilitate administrative processes or plug communication gaps. Nevertheless – or precisely because of their omnipresent visibility – they often fade into the background; who thinks of the software that fills windows with text during a chat? The email inboxes of curators while visiting an exhibition? As ‘silent’ conditions for ‘noisy’ artworks, infrastructures are outsourced to the level of the systemic. This overlooks the fact that the dimensions of institution, infrastructure, architecture and interface always represent a form of active involvement rather than merely acting as a passive condition. Taking a performative, action-oriented interpretation of infrastructures as a starting point, I was interested in everyday practices that co-formulate institutional infrastructures as well as the archive of institutional narratives that in this way continuously grows with them. This led me to the study of the phenomenon of gossip, an everyday practice often dismissed as inferior, whose presence in the narrative of an institution is usually neither explored nor even acknowledged. Scandals involving executives are an exception – but as a conscious strategy or self-(re)produced part of an institution’s image, gossip hardly receives any attention. Gossip, I claimed with my annual curatorial program of the same name in 2021, makes institutional infrastructures and memories visible that were otherwise barely noticed. How does gossip thus institute an ephemeral, invisible archive of an institutional narrative? And how does this archive resonate with communal infrastructures?

1 Braidotti, Rosi: From Nomadic Theory. In: Aloi, Giovanni / McHugh, Susan (eds.): Posthumanism in Art and Science. New York: Columbia University Press 2021, 40-43, 40.

2 Berlant, Lauren: The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2016, Vol. 34(3), 393–419, 393.

3 See Federici, Silvia: Caliban and the Witch. New York: Autonomedia 2004, 221.

4 Black, Hannah: Witch-hunt. Gossip has always been a secret language of friendship and resistance between women. In: Tank Magazine / The Gossip Issue, Spring 2017, 107–110, 109.

5 Butt, Gavin: Between you and me – queer disclosures in the New York art world, 1948-1963. Durham: Duke University Press 2005.

6 Siegel, Marc: Gossip is fabulous. Queer Counter-Publics and “Fabulation”. In: Texte zur Kunst, Issue 61/ Gossip, March 2006, 116–121.

7 Siegel, Marc: The Secret Lives of Images. In: Hagener, Malte / Hediger Vinzenz / Strohmaier Alena (eds.): The State of Post-Cinema. Tracing the Moving Image in the Age of Digital Dissemination. London: Palgrave Macmillan 2017, 195–210, 196.

First of all, gossip was interesting to me precisely because it had negative connotations: as unauthorized, legitimate knowledge, as marginal, enigmatic, perhaps peripheral. To program an institution in a rural area meant working beyond the urban art centers with an audience whose knowledge of art was not necessarily pre-educated. I was in a context that was called periphery – but with the thematic setting on gossip, this context began to develop its own language and release knowledge. The narrative of the foundation was linked to a white man, the successful pharmacist and hobby artist Arthur Boskamp. This focus on the white male entrepreneurial figure was meant to be changed with GOSSIP. Accordingly, I referred to a definition of gossip as formulated by feminist and queer theorists. In “Caliban and the Witch,” Silvia Federici shows how in modern sixteenth-century England the term “gossip” was first used pejoratively to undermine exchange and solidarity among women*.3 During the Middle Ages, gossip was used to refer to a close female friend. Federici attributes this to the rise of capitalism, which excluded women* from the public sphere in order to exploit their reproductive labor, now understood as private, and to tie property relations to gender. Gossip was seen as an attack on these relations, as it formed an alliance between women* beyond the relationship of wife and husband – and, according to Federici, can be seen as perpetuating discrimination and persecution against women*, as was done with the witch hunts of the Middle Ages. For me, this devaluation was an important starting point, because it was followed by possibilities of solidarity and invisible alliances within and beyond institutions. I wanted to explore the resistance of gossip that is created through the formation of counter-publics; elusive, marginal publics based on trust rather than authorization, on informal gatherings and the uncontrolled circulation of content. When artist Hannah Black writes: “The gossip, like the witch, was persecuted as if she were an outlaw, instead of at the heart of her community. Her superpower is hanging out – giving, sharing, spending and wasting time together”,4 then I wanted to explore these gatherings as the perpetuation of a previously invisible archive on an institutional level as well. I related to queer and feminist approaches as Marc Siegel and Gavin Butt5 formulated also in reference to the art world. Siegel underlines the subversive power of gossip in queer subcultures of the 1980s6 and emphasizes its speculative momentum: “Gossip, I argue, is not simply a means of oral communication but rather a speculative logic of thought […] and central to the construction of identity and intimacy in queer counterpublics.”7 As a consequence, gossip has a performative and transformative effect on the relationships of individuals, institutions, and media; it changes one’s own self-images and narratives by circulating speculations about others. Taking a closer look at the projects that took place at the M.1 of the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung in Hohenlockstedt, this circulation and proliferation of narratives against the backdrop of both a very present family history and a public institutional mission became the core of the program GOSSIP in 2021. Working in a Foundation that is named after Arthur Boskamp and run by his daughter Ulrike Boskamp, I was facing the legacy of a family: their internal relationships and embeddedness in the region. More precisely, the absent eponym symbolizes next to his passion for art the history of the place itself, a history that is interwoven with the military, with the German economic miracle of the postwar years, and with power in general. When Arthur Boskamp took over his father’s business in 1945, he ordered the company to flee from Danzig to Schleswig-Holstein to escape the Red Army. In what was then Lockstedt Lager (today: Hohenlockstedt), he acquired former military quarters from the Kaiser era and began building the current company headquarters there to produce gelatin capsules and other cold preparations in a former SA sports school. I questioned, how could this embeddedness in the local history of military and capitalism speak back to the institution?

Understanding GOSSIP as a strategy of curatorial research, the development of mediation strategies that discuss, dismantle, and recompose the dominant narratives of the institution became the core of the program. These narratives were put in relation to vernacular, non-institutionalized forms of communication to explore their potential of instituting new narratives – thus disseminating a fluid, speculative archive of communal infrastructures. Taking the Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung as an exemplary case study, GOSSIP investigated how those narratives are composed – and how they can be transformed into a speculative scenario. First of all, the narrative of the institution followed Arthur Boskamp on one hand, and the authorship of each Artistic Director on the other. Both were rooted in the patronage of an individual subject and in the role of the artist as creator. GOSSIP, I assumed, could queer these narratives by shifting the perspective from the role of the individual creator to the collective and decentralized act of storytelling. Queering here denotes the reiteration and reinterpretation of powerful fixed orders or (pre-)images, an “undoing [of] ‘normal’ categories,”8 as Donna Haraway calls it. Based on this focus on the parameter of gender, I use the term queer as an action practice of queering to reinterpret actions, gestures, and behaviors that follow white cis-male dominance, heteronormative structures, and a neoliberal logic through a curatorial program: a (re)ordering. My hypothesis was that within institutions, gossip functions as a form of invisible archive in relation to informal infrastructures that are constantly in motion, and that produce them under certain social, economic, and artistic conditions.

The programmes of each Artistic Director tell new stories about the institution with each directorship. Through such, the curatorial programmes create a narrative of continuous institutional flux. In this context, stories can be defined with Swedish literary theorist Lars Elleström as “a media product providing sensory configurations that are perceived in a meaningful way.”9 Stories are therefore less framing, but rather interpreting; they lay out a narrative in a sensually perceptible way and produce concrete, significant experiences. I linked these experiences in various formats to compose a specific dramaturgy, starting with one in which I myself would have no control over the plot of its story: an Instagram takeover of @m.1arthurboskampstiftung by students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig.

The first thing to queer my program was my own authorship. I took gossip programmatically, which meant I wanted gossip to determine the program. For this, content should become visible that was beyond my control, had a momentum of its own, and was not co-produced by the foundation. Following the determinant factor of time, the narrative of the foundation was described via Instagram with new stories at the start of the program. GOSSIP became a self-explanatory system error: it was not about the upcoming program within the foundation, but about debates within the Academy that were current at the time, such as the abuse of power and neoliberal productivity constraints. Under the title Institutional Glitches, the temporary takeover made clear that the circulation of manipulated information no longer takes place backstage, but has become an visible part of networked infrastructures in which institutions are also involved. Based on Legacy Russell’s notion of glitch10, the accidental error that indicates the radical failure of a system, the intervention accelerated and distorted the images of the foundation by shifting the narrative to the students’ personal needs and politics. Their inhabitation of the Instagram account showed how every system of representation is a multivocal system of intersubjective speaking positions that comment, repeat and rate each other. The narrative of the foundation, which I had been assigned to update and continue, initially dissolved into a cloud of social media buzz.11 Narration took place through communication and media products. It turned out that it was not the stories that changed – the students remained in the script of their university, so to speak – but the narrative within which they were articulated. The same story was thus transmitted in different narratives; but due to a shift of medium and speaking position, they could articulate critique in a transmedial way. “Silence is violence”, one of the posted stories claimed (Figure 2), made clear how the takeover contributed to an institutional archive of untold stories: stories that are not necessarily part of the foundation, but could traverse different institutions, stories that address systemic abuse of power positions, stories that made visible the immateriality of artistic work and unpaid labor by posting links to the students’ Paypal accounts (Figure 3). Sunny Pudert and Shirin Barthelt recorded videos, which hinted at explosive content without ever saying it. As a consequence, they continued with their Instagram Reels as a viral strategy to comment on the program. After the takeover and in cooperation with the online art magazine KubaParis, their dialogue-like clips were posted under the title The Gossipers, parodying the supposedly detached judgement of art criticism with strong filter aesthetics and effects (Figure 4).

8 Haraway, Donna: Foreword. Companion Species, Mis-recognition, and Queer Worlding. In: Giffney, Noreen (Hg.): Queering the Non/Human. Hamoshire und Burlington: Ashgate 2008, xxiii- xxvi, xxiv.

9 Elleström, Lars: Transmedial narratives and stories in different media. Cham: palgrave macmillan 2019, 35-43.

10 Russell, Legacy: Glitch Feminism. A Manifesto. London, New York: Verso 2020

11 David Joselt speaks about ‘buzz’ that defines the value of art in the digital age: “In place of aura, there is buzz”. Joselit, David: After Art. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press 2013, 16.

Fig. 2

Institutional Glitches, April 2021, Instagram screenshot

Fig. 3

Institutional Glitches, April 2021, Instagram screenshot

Fig. 4

Institutional Glitches, April 2021, Instagram screenshot

12 See Philips’ conception of storytelling as a scientific method of storytelling: Louise Gwenneth / Bunda, Tracey: Research through, with and as storytelling. New York: Routledge 2018, 1–16.

13 Lothian, Alexis: Old Futures. Speculative Fiction and Queer Possibility. New York: New York University Press 2018, 1–29.

14 Translated from the German original: „Geblieben ist ein großes Archiv und die Farbe Gelb, die jemand mochte. Und Arthur sah und sprach es werde Kunst, und es ward Kunst für einige. Und Arthur sah alles was er gemacht hatte und – . Doch heute gibt es M. und M. sind viele. In M. ist vieles anders und anders ist auch die Kunst.“

Fig. 5

Workshop THE SPECULATIVE INSTITUTION, M.1 Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, June 2021. Photo: Marie-Theres Böhmker

The first perception of my program was thus not a statement, as it is often done with exhibitions, but a loss of control that gossip often represents – and likewise the empowerment of voices that are not heard in this form in other infrastructures. I went further with this form of curating as an exploratory searching movement. I understood everyday stories as a scientifically and artistically relevant object that contrasts tested, situated knowledge with authorized narratives.12 In the sense of Louise G. Philipps and Tracey Bunda, storying, the verbification of the word story, advances to a counter-strategy of dominant narratives: stories live from being retold, from their communities, and have no superior scheme of meaning. It is based on local and situated truths. As a consequence of starting the program with a loss of control and increased social media traffic, I was interested in how the foundation’s narrative could be understood more as speculation directed into the future than as knowledge transmitted from the past. Since infrastructures usually anticipate the manifestation of future conditions, they are genuinely speculative scenarios.

Speculative scenarios often point to the digital, or to a fictional understanding of time, which above all conditions queer, non-linear chronologies.13 Chronologies are rarely interrogated in the self-image of institutions beyond a founding myth or a history of progress. Together with Fiona McGovern, I thus invited students of Cultural Studies and Cultural Mediation from the University of Hildesheim to take a closer look at the institutional narratives of the foundation. Based on locally situated and in-family, narrative-embedded stories, the students investigated how such stories were composed – and how they could be transformed into a potentially speculative scenario (Figure 5). The students developed a hypothetical mediation strategy consisting of an abstract, multi-vocal video conversation that highlighted a narrative that emerged from overlaps and superimpositions, anecdotes, gaps and questions. They combined image and text in a fragmentary and unfinished way. In doing so, they mixed different temporalities and speaker positions. Most of all, they rewrote and continued statements by Ulrike Boskamp, who had told the story of the foundation. The students combined history with storytelling and used these extracted, fragmentary anecdotes to refer affectively to individual places in the M.1, such as “the whirring of the refrigerator”. In this way, they created a new story that circulated around the institution, creating distance from the original narrative through the repetition of statements. The result was a subtle parody and critique in the form of a continuously moving text-image collage. For example, the students Nina Diehl, Leah Fot, Lisa Hader, Alina Homann and Theresa Tolksdorf referred to Arthur Boskamp and his position of power, from which he legitimized art – including his own – by exhibiting it, as well as the way the building is shaped by personal details such as his favorite color yellow. At the same time, they queered the narrative of Arthur Boskamp as founding father by opposing him with a multiple “M.” that cannot be traced back to one person, spoken in a fragmentary form:

“What remained was a large archive and the color yellow that someone liked

And Arthur saw and said let there be art, and there was art for some

And Arthur saw everything he had made and –

But today there are M., and M. are many

In M. many things are different and different is also the art”14

Critically questioning the relations of guest and host within institutions, the students discussed, dismantled, and speculatively recomposed dominant narratives, by making gaps in the history of the institution a visible part of their affective form of storytelling.

Fig. 6

QUEER BAR, M.1 Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, August 2021. Photo: Paul Niedermayer

A third example for the queered narrative of the institution is the project QUEER BAR. Hosted by the artist Paul Niedermayer,15 the QUEER BAR’s understanding of time, in the sense of Jack Halberstam, assumed that time is perpetually present. It is neither fixed on the reproduction of history nor on reproduction as its primary goal. Just as, according to Halberstam, queer time leaves frames of bourgeois reproduction and crosses different temporal planes,16 queer space leaves the binary logic of center and periphery to create counterpublics starting from the supposed margins. In the countryside, where queer people usually do not occupy much space in the sense of a visible, publicly accessible place, the QUEER BAR opened up the possibility of coming together at a shared, transgenerational community space. Through this coming together, it formulated resistance to prevailing narratives of invisibility of LGBTQI* persons in the countryside, while equally undermining a heteronormative understanding of time through the different generations. Against this background, Paul Niedermayer transformed the garden of the foundation into a bar in which familiar furnishing elements from local gastronomy were recombined with lighting elements and objects designed by the artist.

Each episode of the QUEER BAR contributed to both an existing and new infrastructure in continual creation of relationships, and blurred the boundaries between familiar and foreign. QUEER BAR signified queer possibilities for reinterpreting the present narrative, or the fiction of a possible future intertwined with the present. The bar’s resistant moment is its chrononormativity, the way in which experiences follow patterns over time in conformity with a (hetero)normative framework. This framework became recomposed by old elements; just like old stories that are re-told in order to create a new narrative. This narrative was community-based, queer, and never predictable: it continued from event to event by the guests themselves, who constituted the space through their conversations and stories. This ephemeral building of a queer community, often perceived as invisible in the countryside, became part of the institution’s archive and its infrastructures.

The formats of the social media takeover, the workshop and the bar reveal that institutional infrastructures are not merely a condition that can be used differently. They make clear that the way they are used reinterprets infrastructures and thus also retells them.

As events, they released space in different ways to queer the narrative of the foundation through exchanges, gatherings, conversations, and storytelling. Their invisible dimensions thus emerged and inscribed themselves in the Foundation’s ephemeral knowledge. Through their power-critical agenda, they told stories of otherwise locally invisible perspectives. They added alternative narratives to the site’s military and corporate history by formulating an infrastructure that defied control and calculation. This can be understood as a reiteration of invisible infrastructures already laid out by the Foundation, but were overwritten with authorship by the namesake, artists, and the curators. Gossip was thus deployed as a means of traversing different media and spaces and making this knowledge visible through new relationships. The field of the curatorial, which understands strategies of becoming public as forms of producing meaning by continuously rearranging and (re)combining contexts,17 can be seen as a method of making these – supposedly invisible – relations visible, and with them their political dimensions and infrastructural dispositions. In this sense, institutional narratives, just like gossip, have no clear origin, but unite object and addressee in a shared moment of re-telling. The narratives constituted by the program deviate from the institutional guidelines, which are strongly tied to persons – the respective Artistic Directors, as well as the eponym Arthur Boskamp. Rather, GOSSIP revealed how infrastructures always represent a form of common use that leads to new interpretations depending on expectations, perspectives of use, and medium. The image of the institution as a UFO, which I encountered at the beginning of my curatorship, is therefore the potential of the Foundation: it enables speculative, ephemeral modes of becoming visible of what was previously invisible.

15 Since 2022, the queer bar continues in a more self-organized way. It is organized by Agnieszka Roguski and Paul Niedermayer and co-hosted by people from the local queer community.

16 Halberstam, Jack [Judith]: In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives Sexual Cultures. New York & London: New York University Press 2005, 1-22.

17 Thus Beatrice von Bismarck states: “The curatorial is the dynamic field where the constellational condition comes into being.” Rogoff, Irit / von Bismarck, Beatrice: Curating/Curatorial. In: Bismarck, Beatrice von / Schafaff, Jörn / Weski, Thomas (Hg.): Cultures of the Curatorial. Berlin: Sternberg Press 2012, 21–38, 24.

Fig. 6

QUEER BAR, M.1 Arthur Boskamp-Stiftung, August 2021. Photo: Paul Niedermayer